'The most terrible poverty'

Peter Waddup, CEO - The Leprosy Mission Great Britain

Mother Teresa once said “Loneliness and the feeling of being unwanted is the most terrible poverty". It is not until I began spending time with leprosy patients that I realised what it might be like to feel abject loneliness. Or to experience the desperate poverty of being unwanted and unloved.

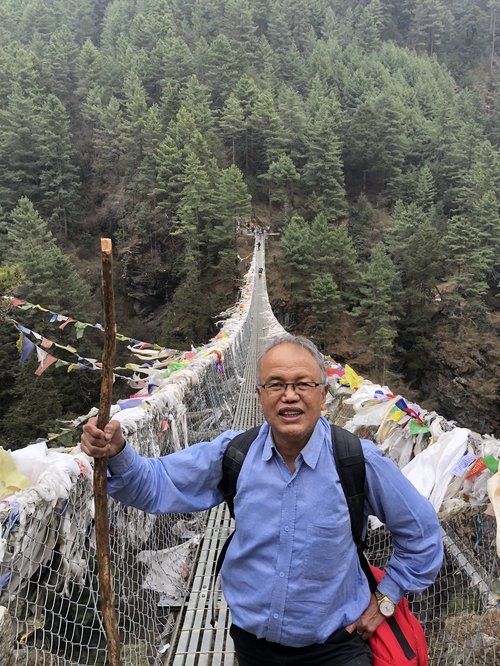

You might have already seen that I was in Nepal last week with a group of UK supporters at Anandaban Hospital. I can safely say the group had a week they’ll never forget! Soon after we arrived, wildfires that had been burning in the forest for days accelerated. The blaze was heading towards the hospital at an alarming pace. So much so that an emergency evacuation plan was put in place. But first we would need to move the patients from the ward nearest the flames to the far side of our hospital campus. The UK team quickly rolled up their sleeves and disinfected an unused ward for the patients to shelter in. We then reluctantly took the advice of the hospitals management. Realising there was little more we could do to help, we left for the nearby city of Kathmandu with heavy hearts.

You would think this alarming start to the week would be the memory most etched on the minds of our visiting team. But it was in Kathmandu, safe in the knowledge that the flames had been arrested just metres from the hospital, they heard an unforgettable story. It was quite by chance that Pastor Lok popped into The Leprosy Mission's Patan Clinic. The satellite clinic in the heart of the city is the first port of call for someone with leprosy symptoms. Lok had heard about the fire at Anandaban and had dropped into the clinic to see if he could help. I have met this amazing man before and called over to him to say hello. We chatted and he ended up telling the group his story. They listened with such intent you could've literally heard a pin drop.

Lok comes from a poor and remote community in Nepal. Yet his family had a real standing in the community with his father being the village leader. It was when Lok's mother was pregnant with him that she showed signs of leprosy, a much-feared disease. She was banished to the cow shed to protect her family. After Lok was born he was taken from his mother and raised with his brothers and sisters.

It wasn't until Lok started school that he was reunited with his mother. Yet in the saddest of circumstances, Lok too began showing signs of leprosy. While mother and son could now be happily reunited, they would be outcasts together in the cow shed. They were not allowed to touch other members of the family or play with them. Lok described them as being like dogs infected with scabies. They felt such shame about their condition that when people visited the family home they hid. Without the cure for leprosy, the health of Lok and his mother, drastically deteriorated.

A few years later when he was around the age of 12, a man came to Lok's village and caught sight of him. He told Lok's father of a place where he could get leprosy treatment. The news soon spread around the village and was welcomed by two men with symptoms. The two men and Lok would travel to the hospital together. Sadly Lok's mother was too ill to make the journey and, being the wife of a village leader, there was simply too much shame.

There was no transport and it took 13 days to walk to the hospital. Lok seriously didn't think he'd survive the journey. His mother packed him a sack of essentials including rice and a small pot to cook in. She struggled to walk, in tears, with him for the first two hours where Lok met his two travel companions. But what hurt Lok the very most was that nobody else came to say goodbye to him. A young lad of 12 making a perilous journey alone. Fifty years later, he could not stop his own tears when recalling the day he left his village.

I'd like to report that life got easier for Lok once he started taking leprosy treatment but sadly it didn't. He developed a painful reaction to the dead leprosy bacteria in his body which made him cry out in pain. He was prescribed aspirin to dull the pain. He eventually became so desperate and ashamed of his 'disgraceful life' that he took every single pill at once. Thankfully he vomited and survived.

After reaching rock bottom, by his own tenacity and the grace of God life slowly improved for Lok. Happily he fell in love and got married. He now has two grown up sons who is immensely proud of! Although he struggles to hold a pen because of nerve damage caused by leprosy, he even went back to school. He became a Christian and found strength through his faith. And while leprosy has caused untold damage to his body, he is now cared for by the amazing team at Anandaban.

While Lok's story has a happy ending and he now knows love, happiness and acceptance, his wounds are deep. When a supporter put their arm around him, he looked visibly shocked that they would choose to touch him. And this is 50 years later. Watching the group of UK supporters, tears running down their faces, I was struck that Lok is one of the fortunate ones. Despite all he had been through, he had come out the other side whereas so many do not.

A few days later we were visiting a community affected by leprosy with Ruth, the wonderful counsellor at Anandaban. It was telling how many people we encountered who asked for Ruth’s help. Although these were people who, like Lok, were through the worst, they still struggled with the pain of loss and rejection.

In the run up to Mental Health Awareness week on Monday, it is my hope that every Leprosy Mission hospital can have its own counsellor. I am in complete awe of the medical team at Anandaban. Their skill in nurturing bodies back to health after leprosy is incredible. And the compassion and love they show to everyone they treat is so moving. Yet I still feel with leprosy that the deepest wounds are the ones that patients internalise. Every leprosy patient needs and should have access to a Ruth.